This review contains spoilers (I wanted to dive deep and discuss the film in a thoroughly meaningful way). Here’s the non-spoiler review: It’s damn good. Go watch it.

When I was a kid and throughout my teenhood, I did a lot of hiding. While I was at school, I always hid the fact that I understood Tamil and emphasized that I come from an English speaking family. I pretended that I didn’t watch Tamil movies (heck, I laughed along with friends and acquaintances when they ignorantly poked fun at Indian cinema) and immediately, with urgency and panic, switched the channels of the radio in my grandfather’s car from a Tamil channel to an English channel if a friend would carpool with me. Now, I wasn’t lying, not exactly. I do come from an English speaking family, I can’t speak Tamil beyond ordering food at a restaurant and asking for directions (I understand the language, though) and I do primarily follow Western pop culture. But why did I feel the need to emphasise certain aspects of myself and hide others? Why did I hide the fact that I understand an extra language? Shouldn’t that be something I show off (after all, I proudly gloated to the world, with a big fat smile on my face that I understand Mandarin)?

Why did I pretend?

Why did I pretend that I didn’t watch Tamil movies when 90s Rajinikanth played just as big a role in fueling my passion for film as Star Wars and Harry Potter? Why did I hurriedly switch the classic song from an old Sivaji Ganesan movie that my grandfather was listening to, to Black Eyed Peas the moment a friend put his foot in the car. It’s my grandfather’s car after all, not my friend’s. Because I didn’t want to be associated in any way, shape or form with them. By them, I mean ‘Indians’. I didn’t want my schoolmates to see me as a scary guy, a gangster, a potential drunkard, a thief. No, of course not all Indians are like that — being a criminal isn’t race specific — and I knew that even back then. But that’s how the obtuse Malaysian masses saw (still see) the Indians, isn’t it? So, instead of us, even I called Indians them. I hid and I pretended. Sometimes I was white, sometimes I was Chinese, but never in school at least, was I Indian. So much so that when a friend of mine said (and this was when I was 12, mind you), “you know, you’re pretty awesome. You’re not like them at all. You don’t smell like them too. You’re different,” I took it as a compliment.

A fucking compliment.

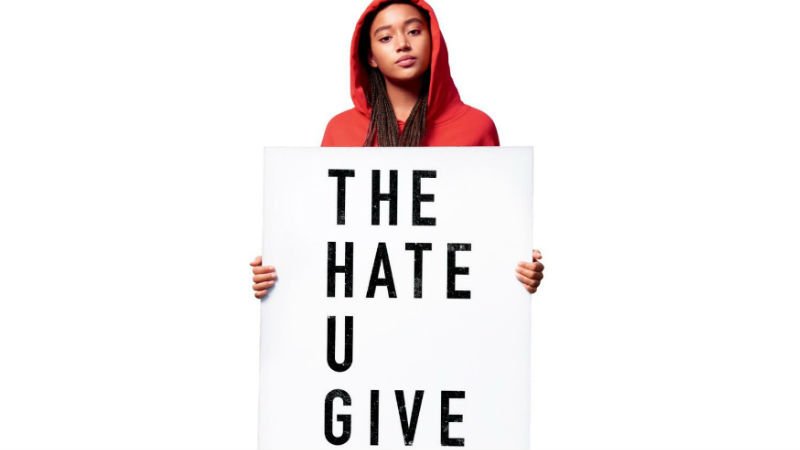

Of course, a few years ago (yeah, only a few years ago), I let that ship sail and sink to the bottom of the ocean. No more pretending, no more hiding behind a veil. But I tell this story because George Tillman Jr’s The Hate U Give (based on the book by Angie Thomas) struck a major chord with me. It opened the floodgates and brought back memories.

We often see black oppression films told from the perspective of adults. The Hate U Give is a unique film about racism, oppression and more importantly, IDENTITY, told from the perspective of a modern middle class teenager. Starr Carter (Amanda Stenberg) is a black youth who lives in the ghetto. In it, there is a school — Garden Heights — where youths go to get jumped, high or pregnant. She doesn’t go there. She and her siblings go to a private school in a primarily white affluent neighbourhood — Williamson Prep — in which she, just as I did, does a lot of hiding and pretending. (Though, there’s a strong reason for her identity switching — she witnessed her best friend get shot when she was only 10 years old and her mother said, enough is enough. You can discover the remaining details of this subplot when you watch the movie, which you are going to do, when it’s released in cinemas.) Her hair is braided and kept down and she doesn’t speak in ‘black’ slang (i.e Yass, homeboy, fleek, etc). Ironically, the white teens around her do. “When they talk like that, it’s cool. When I talk like that, it’s hood.” It’s a stinging line!

When we first meet Starr, living two identities is already second nature to her. Her only constant is her favourite pair of Air Jordans (cool in both black and white neighbourhoods). Williamson Prep may not be a life-threatening place — you don’t have to worry about being shot at — but for a black teenager, it’s still not easy. When Starr hangs out with her white boyfriend (K.J. Apa basically playing Archie Andrews with black hair), people stare at her. They don’t say anything, of course, they don’t — they’re too “classy” for that — but you know what they’re thinking, just by the way they look. What she doesn’t realise at that time, is that her life is going to get a helluva lot more complicated.

One day, as she’s cruising around the neighbourhood with her childhood best friend and first crush, Khalil (Algee Smith), a cop pulls them over. A white cop. They tell the cop that they’ve done nothing wrong (they really did not do anything wrong), but the cop orders Khalil to step out of the vehicle anyway. And in a haunting sequence of events, Khalil is shot dead. You see, the cop assumed he was carrying a weapon, when in actual fact, he was merely holding a hairbrush. This is where our narrative truly kicks in, as Starr’s life begins to spiral out of control and she’s forced to make difficult choices.

Should she testify in front of a grand jury; Should she go to the media? The simple answer is yes, she should. If she does, she gets to be Khalil’s voice and hopefully, help in the pursuit of justice, not just for her best friend, but also the many, many innocent people in her community who have been shot at by white cops (sometimes black cops too). But The Hate U Give is a complex film. It observes and comments on all sides of the spectrum in great detail. Here we see that by speaking up, everybody in her school will label her as ‘the black girl from the hood who saw her friend get shot.’ The label she worked very hard her whole life to avoid. But if she doesn’t, then her deceased best friend and his family don’t have the only eyewitness of the shooting standing up for him. (It also means having to deal with the emotional toll that comes with burying the incident and the trauma deep inside of her.) But there’s also another side she has to consider. A far more dangerous side. Speaking up for Khalil would also mean speaking up against the biggest drug dealer in the neighbourhood (Anthony Mackie).

But why? You might ask. Why is it so important to her and her mom that her second identity is kept intact? We look at Starr’s mom (Regina Hall) and dad (Russell Hornsby) and their contrasting parenting styles. When Starr and her siblings were just little kids, their dad gave them the talk. But unlike a lot of our families, “the talk” doesn’t mean ‘the birds and the bees’. Here we see Mr Carter telling his children what to do when a cop pulls them over — not if but when. “Put your hands on the dashboard, where they can see you and know your rights!” He also tells them to memorise the Black Panther Ten-Point Program, which includes “an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people” and “… to work for justice by any means necessary.” “By any means necessary!” he makes them repeat. Later in the film, he tells Starr, “When you’re ready to talk, you talk. Don’t let nobody make you be quiet.” He believes that when the time comes, Starr should put her foot down and speak up against injustice, however dangerous that may be. For Starr’s dad, it’s about improving your lives from within the community — it reminded me of Kaarikalan’s philosophies in Kaala.

For Starr’s mom, it’s about the most efficient way out of the mean streets of the ghettos. Go to a private school, keep your head down and your blackness buried, study hard, play by the rules no matter how fucked up they are, work within the system that’s rigged against you from the top bottom, go to college, get a degree, get a job. It’s a far more realistic and calculated approach — think of the philosophies in Pariyerum Perumal. And this is why I love this film. The Hate U Give may be about black and white people but its narrative is painted in grey textures. Angie Thomas and screenwriter Audrey Wells don’t write Mrs Carter as someone who’s wrong. Her principles don’t stem from cowardice, but survivability.

The cruelty and injustice that befalls Khalil bring out everybody’s true colours. People always seem all sunshine and rainbows until shit hits the fan. Take Starr’s ignorant white friend Hailey for instance, who when watches the news of the cop who shoots Khalil says, “well, the cop has rights too.” In another scene, she tells Starr that the hairbrush looks like a weapon “in his [Khalil] hands.” It harkens back to the theme set earlier in the film about how the same type of language used by different groups of people, is perceived differently. A hairbrush in the hands of a white person is just a hairbrush, but in the hands of a black, it’s a weapon. Hailey also tells Starr “but you’re not like them…” But Starr, unlike myself, doesn’t take that as a compliment, rightfully so. Through these events, Starr sheds her second identity, she removes her veil and finds her voice — and boy, is it an emphatic voice! (Note: The film doesn’t vilify white people. Starr’s boyfriend is white.)

People always use the word ‘colour-blind’ to describe non-racism. But what does that term truly mean? Does it literally mean to turn a blind eye towards colour? Because to be blind is also to be ignorant, like in the case of Hailey, who is ‘colour-blind’ so long as it fits HER narrative. The true meaning of colour-blind is explored and defined through two beautiful scenes that parallel each other. The first one takes place at prom. Black-haired Archie tells Starr that he doesn’t care about colour, to which she responds “if you don’t see my blackness, it means you don’t see me.” Being colour-blind isn’t about being oblivious towards one’s colour. It’s about seeing it — and the culture that comes with it — and embracing it wholeheartedly. Black-haired Archie responds “I see you,” in one of the film’s most beautiful moments.

On the flip side, when Starr tells her dad that she has a white boyfriend, her dad is shocked — almost rendered speechless — and a little heartbroken. Her dad isn’t racist the same way Hailey or the police officer who shot Khalil is. But he, just like many of our parents would much rather see his daughter be in a relationship with someone of their own skin colour. “I thought girls usually like to date men who resemble their daddies. I guess I didn’t set a good example of what a black man should be.” To which Starr replies, “No, you didn’t. You set a good example of what a MAN should be like.” It’s a wonderful piece of exchange that ties both scenes on colour-blindness in a poetic manner. At the end of the day, what matters is who you are beyond your biological traits.

But more than anything, this film is about Thug Life. We see the phrase being thrown around frequently. We see it in memes (below).

But what does Thug Life actually mean? 2Pac famously once said, “The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody. T-H-U-G-L-I-F-E. Meaning what society gives us as youth, it bites them in the ass when we wild out.” It’s a powerful line and it is both the core of Angie Thomas’ book and this George Tillman Jr film. We associate black people with gangsterism and crime. But how often do we look at the root cause? Think about it. The whites kidnapped the Africans and brought them to the US, enslaved them and forced them to fight their wars. Even when slavery was abolished, for the longest time, blacks were denied their basic right to an education and to vote (see Selma). They were forced to fend for themselves without jobs in the ghettos. But when they look at other means for income, say drug dealing, we turn around and call them criminals. How wonderful. When cops kill innocent black kids, the hate these kids have been given screws us all. Anger. Backlash. Riots. More innocent blood spilt. This will not happen if we treat people with love. “How many of us have to die for y’all to get it?!” We can’t solve problems with hate. The film comes full circle right at the end, when a little boy points his father’s gun…

The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody.

I love this film for its importance. I also love it as a movie. I’ve spent so much time talking about the cultural significance of the film, I almost forgot to discuss it as entertainment. And it is damn fine entertainment. The Hate U Give could’ve easily been a finger-wagging annoyance, but it isn’t. This is a character driven drama that is gripping, emotionally moving (I broke into tears many times), haunting and thrilling. It’s easily Audrey Wells’ best screenplay — whose previous notable works are The Game Plan and A Dog’s Purpose, both above average entertainers. But here, of course with the Angie Thomas’ book as a base, she has given us multi-faceted characters and engaging dialogue, many of which are electric. George Tillman Jr (Faster) is also on top of his game. It’s obvious from every frame that this is a project he’s genuinely passionate about.

The performances by Amandla Stenberg, Regina Hall, Russell Hornsby, Anthony Mackie, Common, K.J. Apa, Sabrina Carpenter and Lamar Johnson are good across the board. But the standout is Stenberg. We’ve seen Stenberg as a kid in The Hunger Games. Earlier this year, she delivered a decent performance in The Darkest Minds, a terrible movie. But here, she’s working with the right material and the right director and it shows. She shines as bright as her character name STARR suggests. Here she plays a character who at the start of the film is lost in her own skin, but through the unfolding events that are often painful and uncomfortable, discovers herself. Stenberg delivers a textured performance, showcasing the right amount of rage, insecurities, vulnerability and then confidence.

The Hate U Give is one of the best films of 2018. I don’t know if it’ll wind up getting any awards come next year, but it doesn’t matter. This film, like a lot of stellar films, transcends trophies and statues. In fact, 2018 has been an interesting year for race/religion-centric political films. From commercial outings like Black Panther and Kaala, to smaller, more grounded non-mainstream films like Pariyerum Perumal and this George Tillman Jr picture, this year, more than any other year has taken me on a cultural journey — at times agonizing and uncomfortable, but also full of hope and optimism — and nudged me to look inward and outward; to ponder upon my own identity and worldview perhaps more than I’ve ever done before.

If you’d like to discuss this movie with me you can hit me up on Twitter here: @dashtalksmovies