In the words of media theorist and philosopher Marshall McLuhan, “The medium is the message.” Different mediums in themselves carry different forms and therefore have unique tropes, rules and idiosyncrasies that distinguish them from other types of media. Let’s take The Simpsons franchise for example. An episode of the The Simpsons TV series focuses very little on pacing or plot development, jumping from one event to another for the sake of comedic absurdity. While The Simpsons Movie on the other hand can’t afford to do that, it needs to take character development, story progression and scale into account. Otherwise, it would just be an extended episode of a TV series. It would fail to be a movie. Which brings me to another subject, we need to talk about Netflix’s Death Note.

Receiving mixed reviews from critics and gaining nigh-universal hatred from fans of the original anime and manga, it’s safe to say that 2017’s Death Note isn’t one of Netflix’s better films. Personally, I like the anime, I don’t it love per say, and I was quite invested in it for a good number of years. But that was a decade ago and this time I was ready to give the film a chance. I wasn’t looking for a completely faithful live-action attempt of the series because we already got one in 2006 (which kinda makes this film altogether pointless if you think about it). Regardless I was curious if not excited to see an American take on a beloved piece of Japanese pop culture. How does it fair?

Long story short, it’s problematic. This does not necessarily mean that Death Note is a terrible movie. It’s not. Somewhere in this a film is a competent adaptation that got lost in translation, managing to nail certain elements of the anime on screen and failing in other departments. Here are some things future anime to film adaptations can learn from Netflix’s Death Note.

Stay true to the characters.

The first thing you’ll notice about Death Note is the creative liberties that director Adam Wingard has taken. The setting is a departure from the hectic, performance-based school of Daikoku Private Academy to your archetypal, nameless American high school. Light Yagami is now Light Turner, played by Nat Wolff. Beyond the first name they share though, they are nothing alike. One of the most common complaints people have leveled against this rendition of the anime is the way Light’s character is set up. In the anime, Light is cold, calculative, didactic and self-righteous. Well-intention at first when gifted with the power of the Death Note, he gradually becomes drunk with power, declaring himself a god, Kira. His motivations are complex and his character conflicted. His seemingly caring nature contradicts the way he treats people (like his lover Misa) as a means to an end.

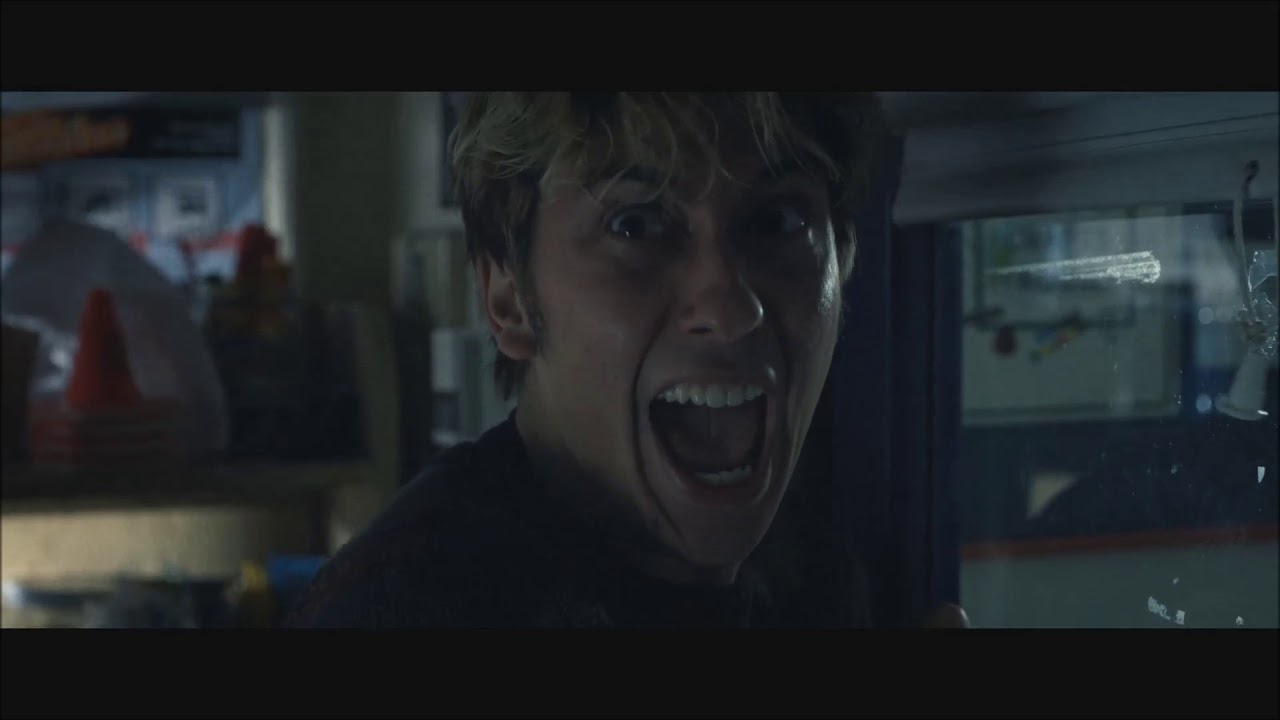

Turner here, however, is a weak, shallow coward. He comes off sounding like a whiny, misunderstood high school brat, using the Death Note for his own selfish purposes like punishing his bullies. He uses the Death Note to impress his high school crush, Mia, before she goes insane and steals it from him. His meeting with the Shinigami Ryuk certainly doesn’t put in a better light either as he comically screams and shrieks upon meeting him. It’s clear to see why fans did not take to this version of Light too well. Light Yagami in the anime plays a pivotal role in propelling the plot forward and keeping viewers hooked. The moment you lose Light, you lose the fanbase.

To be fair however, I did like this version of L played Lakeith Stanfield. In spite of his lack of resemblance to his animated counterpart and propensity for slight overacting, he manages to capture the Sherlockian essence of the character well enough. Lakeith competently mirrors the mannerisms and character traits of the strange candy loving, L. Willem Dafoe was born to play the Death God Ryuk! His voice is perfect for the role, dancing between the creature’s playful and sinister undertones wonderfully. It’s such a shame that the weak link here is Light. L’s relationship with Light in the anime is like that of Holmes and Moriarty. Two respectable geniuses locked in a game of wits. In this case, it’s one respectable genius trying to catch a kid way in over his head. Ultimately, it felt like they failed to understand what made the series so interesting are the characters and the film suffered for it.

Honour the spirit of the anime.

In the past, we’ve seen film adaptations that go above and beyond to bring the world of anime to the big screen. Films like Ruroni Kenshin and Speed Racer truly mirror the aesthetics and style of their source material. Films like Oldboy on the hand serve as more a homage to the original manga than a panel for panel recreation. What all three of them have in common is the respect and reverence they have for the original text. Even if they can’t quite perfect the look of their media counterparts, they exemplify the qualities and principles that they have come to represent. This is where Death Note wavers.

Let’s talk about the positives first. Ryuk looks convincing enough as a Japanese death god an while the CGI is a tad noticeable in some scenes, the design holds up fairly well. It certainly helps that Ryuk is played by Willem Dafoe, who delivers a wickedly fun and energetic performance as the death-loving monster, apple and all. The callbacks to Light’s complicated relationship with his father is also a nice touch, giving the film some emotional weight.

However, the film is devoid of any of the iconic Judeo-Christian and Renaissance symbolism that we’ve come to associate with the anime. In the anime opening, there is a scene that is reflective of Michelangelo’s painting of the Creation of Adam with Ryuk reaching from above to Light. None of that imagery is ever invoked in the film. Neither is the classic church choir score that set the sombre tone of the series ever echoed in Death Note. These visual and audio cues aren’t just there to add an air of class to the anime. It was meant to subtly foreshadow Light’s ascension to the god Kira. The lack of religious motifs robbed the film of its distinguishing factor.

Furthermore, the ethical debate between Light’s consequentialist morality and L’s deontological duty in the anime is noticeably minimized in the film. Briefly touched on in a few scenes, Death Note is content to focus on Light and Mia’s relationship, and the gore on screen. Part of what makes the series so memorable was how thought-provoking it was and its ability to raise interesting questions. Does the good Light bring outweigh his evil? Is L far too rigid in his ideas of the law? Can man handle the power of the Death Note justly? The only question on display here is: How did L know Kira watches the news on TV? Maybe, the guy just uses Twitter.

Tell an original story.

Unlike long-running shonens like One Piece or Bleach, films don’t have the luxury of taking their own sweet, ungodly time. Therefore, film adaptations have to be economical and selective with the story arcs or moments they want to include in a film, lest they go the way 2018’s Fullmetal Alchemist. A bloated and unfocused mess. One thing I do appreciate about this version of Death Note is its attempt at an original story and a subversion of the narrative beats that fans of the series predicted. Granted it wasn’t executed all that well but still the potential was there.

Light’s crush in the film Mia as the emotionally manipulative one in the relationship in lieu of him is an interesting angle. It certainly would make a good twist in the plot if Light had been depicted in a more competent and intellectual manner. The idea of Mia (who is analogous of Misa from the anime) being the more resolved and radical one isn’t a terrible notion. But when it is done at the expense of such a beloved character, it becomes cheap and degrading.

Another subplot that had major potential to be one of hell of a twist was Light’s father, James Turner revealing to his son that he knew he was Kira. Light then explains to his dad how he masterfully planned a series of killings before his comatose state to ensure that he had a solid alibi if the authorities were suspicious. I was certainly shocked by that reveal but the way James found out about Kira’s identity was far too much of a stretch. He just so happened to have found a newspaper cut-out of Skomal, the man who killed Light’s mother, dying in a car accident and in his room and immediately connects that he was his first victim. I’m sorry but that’s a little too convenient isn’t it? That Light is just that sloppy?

This is another prime example of the film sacrificing Light’s supposed “brilliance” in the film for a nonsensical reveal. A far cry from his anime counterpart who ingeniously covered his tracks by hiding a portable mini-TV in a bag of chips as he murders criminals. Managing to fool the authorities by masquerading as a diligent student! If only the film could have spent more time paying attention to the characters and plot coherency instead of trying to be clever themselves. Perhaps then, we could have gotten a worthy entry into the franchise.

Netflix’s Death Note should serve as a cautionary tale to those with the intent of adapting the works of anime for the big screen. They should be a labour of love as much as it is a product of forethought, building upon established foundation without forgetting its roots. A love letter to fans and a bold introduction for the uninitiated. And while I can see an earnest effort on the part of Netflix to add something new to the world of Death Note, alas it needed more than just good intentions.